AUGUSTA — Lawmakers and coastal town officials are calling for tighter limits on the use of a tree-growing property tax exemption that they say is being abused as a tax shelter by wealthy oceanfront landowners.

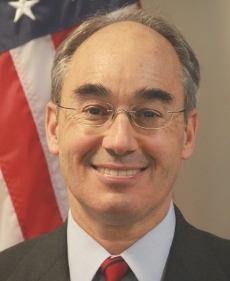

On Thursday, some legislators pointed to one oceanfront landowner in particular: State Treasurer Bruce Poliquin.

Poliquin’s 12.3-acre peninsula in Georgetown was cited in a 2009 state report as an example of the high-value properties fueling local concern that the program is being used to shift the tax burden from wealthy landowners to other taxpayers. It says Poliquin wasn’t necessarily breaking any rules, but may not using the tax exemption as the law intended it.

Poliquin did not respond to requests for a comment about the tax exemption.

The licensed forester who helped Poliquin get the tax exemption in 2004 said Thursday the application was legitimate — there was marketable timber on the land and Poliquin planned to harvest it.

Some lawmakers criticized the deal, however.

“It’s for commercial harvesting,” said Sen. Troy Jackson, D-Allagash, and a commercial logger. “I don’t think it’s to help millionaires have $500,000 tax breaks out on the coast.”

Exemptions for woodland owners mean the rest of a town’s taxpayers have to pay more. That’s fine as long as the landowners are harvesting timber and creating jobs, Jackson said.

If landowners like Poliquin can legally get the exemption, Jackson said, “we need to change the law.”

In fact, the Legislature moved Thursday to tighten up the law.

Members of the Taxation Committee voted 9-0 in favor of a bill to tighten some of the standards for maintaining the exemptions, such as requiring a statement that cutting trees and selling timber is the primary use of the land. The committee also is expected to supprt a second bill, sponsored by Senate President Kevin Raye, R-Perry, to have state foresters do random checks to make sure landowners are harvesting trees as promised.

Members of the Taxation Committee voted 9-0 in favor of a bill to tighten some of the standards for maintaining the exemptions, such as requiring a statement that cutting trees and selling timber is the primary use of the land. The committee also is expected to supprt a second bill, sponsored by Senate President Kevin Raye, R-Perry, to have state foresters do random checks to make sure landowners are harvesting trees as promised.

Maine’s Tree Growth Tax Exemption law has plenty of defenders, as well as critics. It was intended to encourage the owners of woodlands to maintain the land for commercial wood harvesting, a use that creates jobs, limits development pressures and preserves open space for recreation and other uses. There are about 23,000 parcels enrolled in the program, accounting for more than 11 million acres across the state, according to the Maine Forest Service.

“It’s the reason many landowners are able to afford to (pay their taxes and) keep woodlands in the southern two-thirds of the state,” said Tom Doak, executive director of the Maine Small Woodland Owners Association.

Landowners must present a commercial timber management plan and, every 10 years, certify that they are harvesting wood according to the plan. If they don’t comply, the landowners can be forced to pay penalties that may even exceed the back taxes they avoided.

In return for the promise to maintain the woodland, owners get potentially big tax breaks. Instead of taxing the land at its highest potential development value, local tax assessors set the value of the land based on how much the trees are worth.

In the case of oceanfront properties, the difference is huge.

Poliquin, for example, enrolled 10 acres of his 12-acre oceanfront parcel in the tree growth program in 2004. His 4,800-square-foot is on the other two-acre piece at the tip of the peninsula jutting into Sheepscot Bay.

The state report said that the 10 acres, part of “one of the most valuable residential lots in the state of Maine,” was taxed in 2009 at a value of $3,560. The information about Poliquin’s property was added to the state report by the Maine Municipal Association, which surveyed municipal tax assessors for examples of potential abuse. A political advocacy group raising questions about Poliquin’s tax exemption released tax records this week that show the value of his 12 acres dropped from $1.8 million to $725,500 after the exemption. In 2010, Poliquin paid only $21 in property tax on the 10-acre tree-growth parcel, and $17,796 on the two-acre house parcel, the records show.

Despite the hefty tax break, Poliquin can’t produce a lot of commercial timber, according to the state report.

“For several reasons, including difficulty of road access and the restrictions on timber harvesting according to the state’s shoreland zoning regulations, the ability to harvest any timber on this property — even if that was the interest of the landowner — is extremely limited,” the report says.

It is up to local officials to enforce the state tax law, and there is no rush to act in the Poliquin case, said William Plummer, a member of the Georgetown Board of Selectmen who helped review and approve Poliquin’s exemption application in 2004. The board will examine the issue in 2014, when Poliquin has to show that he is keeping up with the timber management plan.

“That’s when the push comes, when these come up for (recertification),” Plummer said. “The selectmen always make sure there’s plenty of paperwork (about harvesting) so there’s no questions. If they come out of tree growth, the fines are there.”

David Schaible, a licensed forester, prepared Poliquin’s management plan eight years ago and said Thursday the land had potential for commercial harvesting, despite its small size and shoreland zoning restrictions.

“There was marketable pulpwood and sawlogs that could be sold following the plan’s harvest recommendations,” he said. “I have not heard from Bruce nor have I been back to the property since March 2004. I do not know whether he followed the plan recommendations.”

Poliquin’s land was cited in the 2009 report before his unsuccessful run for governor or his appointment as treasurer.

As Treasurer, the Republican businessman has been an outspoken critic of Democratic leadership, including the head of the Maine State Housing Authority. The focus on his tax exemption — while coinciding with the legislative debate — is part of a backlash from Democrats, who also have raised questions about Poliquin’s private business activity and his financial disclosure filings.

John Richardson — 620-7016

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story