When Terry Hill needs a permit to build a cabin on her campground, she doesn’t drive to a town hall. She calls a state agency that handles the planning and zoning functions that would ordinarily be handled by a city or town.

That’s how land use is managed in Mount Chase, population 201, located 15 miles from the north gate of Baxter State Park. The settlement falls under the jurisdiction of Maine’s Land Use Regulation Commission, as does roughly half the state.

It has been 40 years since the state formed the commission to bring order to its unorganized territories. Hill said the agency has become a barrier to economic development, and it’s time for Maine’s rural counties to take control of land-use decisions.

“It’s frustrating that people from the other end of the state make rules for how we should live our life up here,” she said.

But transferring oversight from one state agency to the 13 counties in the commission’s jurisdiction would create new bureaucracies and raise taxes in the unorganized territories, said Piscataquis County Commissioner Eric Ward, who lives in the unorganized township of Big Moose.

Moreover, unplanned development scattered throughout the North Woods would boost demand for public services such as snowplowing and trash disposal, and further increase the tax burden, he said.

“I’m telling you that taxpayers — the ones around me — won’t go for that,” he said. “They don’t want to pay more for anything.”

Hill and Ward reflect the two sides of an issue that emerged as one of the most controversial this year in the Legislature.

A study group to be appointed by Gov. Paul LePage and legislative leaders is expected to begin work next month to determine whether the state’s land use commission should be reformed or dismantled. The names of the 13 committee members could be announced as early this week, said Senate President Kevin Raye, R-Perry.

The debate features familiar conflicts: local control versus environmental stewardship, private property rights versus the public good, rural Maine versus urban Maine.

Add to that a heavy dose of partisan politics, the controversy over wind power, the involvement of several environmental groups, and the economic interests of landowners whose property values would jump if regulations were weakened.

Democrats and Republicans in the Legislature clashed this spring over a GOP bill that would have dismantled the Land Use Regulation Commission and distributed its powers to the counties, the Maine Forest Service and the Maine Department of Environmental Protection.

In the end, lawmakers created a group to study the issue and report back in January. The Legislature’s Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Committee will hold at least two public hearings this fall.

Changes in land ownership

When the Legislature established LURC 40 years ago, it was opposed by rural Republicans but embraced by Democrats and Republican leaders, said Horace Hildreth, an early advocate for the commission.

Hildreth, a Republican from Falmouth, was a lobbyist for paper companies before winning a seat in the Senate. He said his former clients opposed his efforts to bring zoning to the unorganized territories. “They liked having a free hand to do whatever they wanted.”

Sixteen corporations and four individuals owned almost all of the land, and unregulated development was threatening to spoil much of it, said a legislative research committee report in 1969.

Today, ownership of the North Woods is much different. Paper companies have sold their holdings, and 79 companies and their subsidiaries, many of which are anonymous, are the major landowners.

The new generation includes investors who are focused less on the long-term timber value of their properties. And the character of development has changed, with modern, four-season vacation homes replacing the traditional, rustic camps that were built there.

Overseeing a vast area

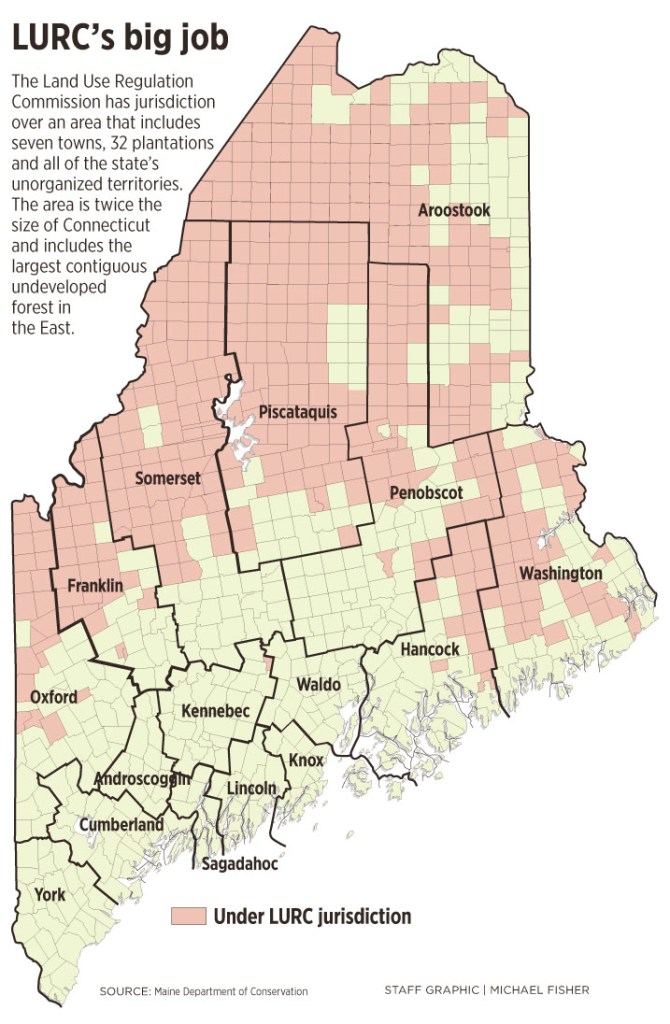

The commission’s jurisdiction covers 10.4 million acres — an area twice the size of Connecticut. It includes seven organized towns, 32 plantations, all of the state’s unorganized territories and the largest contiguous undeveloped forest in the Eastern United States. It includes Matinicus Island, 22 miles out to sea, and 307 other coastal islands.

And only 12,500 people live in the jurisdiction. That’s less than the population of Waterville.

The land use commission has 25 staff employees, with headquarters in Augusta and field offices in West Farmington, Greenville, Bangor, Ashland and East Millinocket. Its independent seven-member board is appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Legislature.

LURC’s jurisdiction is divided into three zones:

* The largest zone, 8.2 million acres, is managed for timber and agricultural production. Residential subdivisions with lakeshore frontage are prohibited. Small subdivisions can be built, only near public roads and within a mile of existing compatible developments.

* Just more than one-fifth of the territory — 2.2 million acres — is in a protection zone, including wetlands, high mountain areas and 500 feet around “high-value” undeveloped lakes. Houses with lakeshore frontage are permitted, but no more than one house per mile of shoreline.

* Less than 1 percent of the land — 41,000 acres — is zoned for commercial and industrial development.

Land in LURC’s jurisdiction has more development restrictions and is worth significantly less than similar land controlled by municipal zoning, said Bret Vicary, an expert in appraising the value of timberland and vice president of the nation’s oldest forestry consulting firm, James W. Sewall Co. in Old Town.

Landowners are interested primarily in forest management, he said, but they are concerned that increasingly tight restrictions and uncertainty about future zoning are undercutting the value of their asset.

Landowners believe that they have little influence in the process, compared with outside groups, and that the current system lacks accountability.

“They don’t have an opportunity to defend their property rights,” Vicary said.

Locals seek control

As an example of LURC’s shortcomings, critics point to Plum Creek’s 975-lot development plan for the Moosehead Lake Region, which took five years to win the commission’s approval and is now on hold because of a court ruling.

A turning point for many critics came in 2007, when the commission held a public hearing on the Plum Creek project in Portland — a three-hour drive or more from where the development is planned.

Last year in Washington County, where 42 percent of the land is under LURC’s jurisdiction, residents were furious when the commission updated its comprehensive plan in a manner that was seen as threatening economic development, Raye said.

He said counties can responsibly assume land-use planning for the unorganized territories.

“The people of my county are good stewards of this earth,” he said, “and I trust them to make decisions about their future, rather than be subject to decisions made in Augusta.”

County commissioners in Franklin, Penobscot, Oxford and Washington counties have voiced support for assuming LURC’s land-use authority.

Counties are better able to allow for local control than a state agency based in Augusta, said Franklin County Commissioner Fred Hardy of New Sharon. He said the current system creates resentment in rural counties.

“As long as the unorganized territories are controlled by a group other than the locals, there will always be two Maines,” he said.

Fix what’s broken

Rather than dismantle the commission, the study group should focus on documented problems and propose improvements, said Pete Didisheim, a lobbyist with the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

Many opponents of the commission appear more interested in opening up the region to development than fixing any problems with the agency, he said.

“If the goal is to maximize the ability to subdivide, then that’s the end of the North Woods,” he said.

The result, he said, would be more restrictions for public access and less timber for Maine’s forest products industry.

Opposition to LURC is motivated in part by resentment of government rules, said Gwen Hilton, the chair of commission.

The commission is not a faceless bureaucracy, she said, noting that all of the commissioners live in rural Maine. She said their job is to enforce Maine law, and they work hard to involve the public in the process.

“We live or work in the jurisdiction,” she said. “We are very familiar with local issues, and our friends, neighbors and relatives are all living in very similar rural places in Maine.”

Catherine Carroll, who has been the commission’s director for the past decade, said LURC, like any agency, would benefit from a top-to-bottom review.

“I welcome and embrace the assault on this agency,” she said.

Tom Bell — 791-6369

tbell@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story