CORNVILLE — On July 4, 1863, Lt. Edwin Barlow Dow, commander of the 6th Maine Artillery Battery, rode across the blood-soaked fields of Gettysburg, Pa., where on the previous three days the most famous and most important battle of the Civil War had raged.

It was the Battle of Gettysburg, with names such as Little Round Top, Cemetery Ridge, Peach Orchard and Trostle Farm.

The United States this year is commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, which began in April 1861.

Dow, who was from Portland, reflected on the carnage that day and marked his own place in history, his descendant, John Dow, 76, of Cornville, said recently. For it was his unit — Dow’s Battery, as it became known — that helped turn the tide in the war.

John Dow said it was Lt. Edwin Dow — his grandfather’s first cousin — who saved the day for the Army of the Potomac on July 2, the second day of the battle, by slicing through the advancing forces of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia with hot shot and powder.

“On July 4th he walked across that field of battle and he made personal notes of what he saw: Horses that were killed and men and the corpses all bloated up. It was a terrible, terrible sight,” John Dow said. “It was unimaginable.”

During those three hot summer days, July 1-3, 1863, about 52,000 casualties were counted in dead, wounded and missing men on both sides of the battle, according to Tom Desjardin, historian with the National Bureau of Parks and Land in Maine. Of that number, 8,000 to 10,000 died. Another 2,000 to 6,000 soldiers died from their wounds, he said.

Unofficial estimates cite 23,000 casualties from a field of 88,000 Union soldiers. Confederate casualties numbered 28,000 out of 75,000 men, according to historyplace.com, an online clearing house of Civil War statistics.

“This was on the second day at Gettysburg, many people say it was the pivotal day — more casualities, more people involved, and it decided the battle,” Desjardin said of Dow’s Battery and its involvement at Gettysburg. “In the middle of the battle line, the Union infantry line collapsed and fled backward.”

A Union artillery brigade, including Dow’s Battery, which was in the middle of the line, plugged the hole, he said.

“They opened fire and stopped the Confederate attack right in the middle of the assault,” Desjardin, who spent six years working at the Gettysburg site, said. “Had there not been this artillery brigade there, there would have been a great big hole and the Confederates would have marched right through it and broken the Union line in half and who knows what might have happened after that. It was very critical part of the battle.”

Maine state historian Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., reading from the 1867 U.S. adjunct general’s report on Gettysburg, said Dow’s Battery indeed played a pivotal role in the outcome of the war.

“At Gettysburg, under the command of Lt. Dow, the battery won an enviable reputation,” Shettleworth read from the report. “It stemmed the Rebel onset when the 3rd Corps fell back. Success was due to the fact that the battery was well directed and produced rapid fire, which both broke the Rebel column and also prevented the Confederates from securing the guns of two batteries they had previously captured.”

Dow’s Battery was just six cannons, or “guns,” as they were called: four 12-pound brass Napoleons and two 10-pound parrot rifles.

Many of the other units in the area had run short of ammunition, but Dow’s Battery had been held back as a reserve unit and was fresh, John Dow said, and had plenty of ammunition.

“He had what they called canisters and he doubled-charged these cannons and they had like 25-30 bullets in each — they’d be like super buckshot and he fired it right into them,” Dow said. “There must have been 3,000 or 4,000 rebels that had advanced. I don’t know how he survived. He was right with them until it was done.”

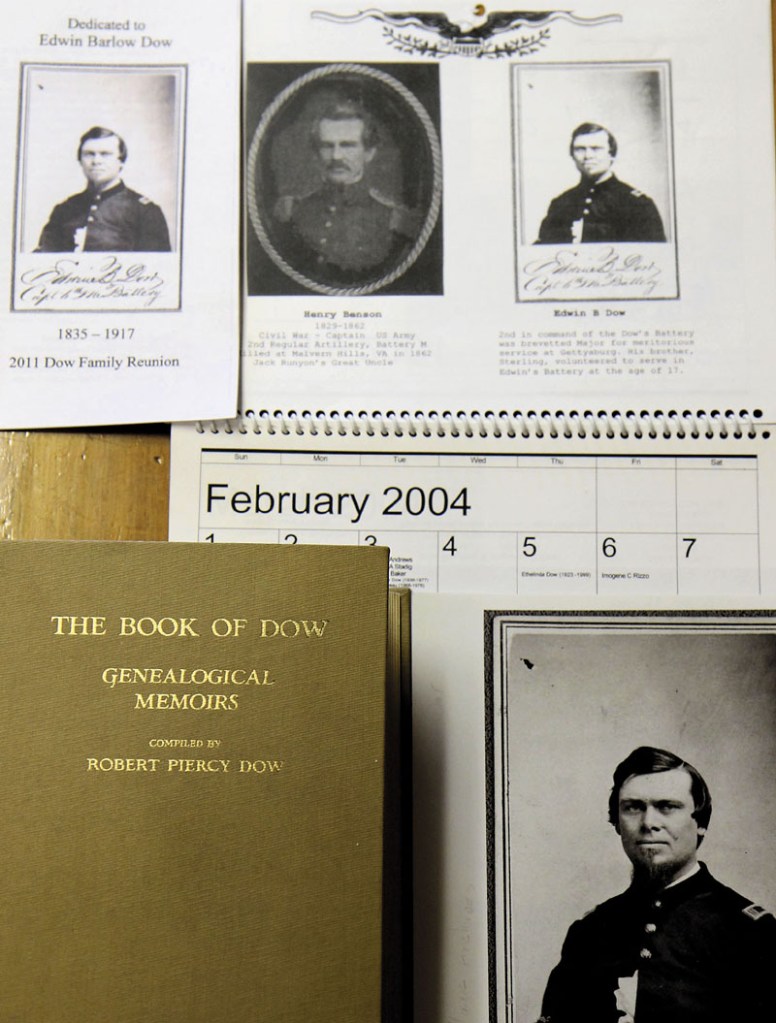

Dow and his wife Betty said they began their research on the Dow family in 2003, when John made a calendar for an annual family reunion, which continues. Edwin Dow is referred to as captain, colonel, lieutenant and major in different historical documents. His rank at Gettysburg is generally considered to be that of lieutenant.

“I learned how important it was when I realized what he had done,” John Dow said. “It’s quite an honor. Up to this point we didn’t think we had any prominent relatives; just common people — boatbuilders.”

A monument also recognizes the deeds of Dow’s 6th Maine Battery at Gettysburg. It stands on what was then the left center of the Union line.

John Dow’s own monument to his ancestor is a booklet he made about the Gettysburg battle and his ancestor that will be distributed among relatives this year at the family reunion.

In that booklet is an interview with, by then, Col. Dow, that appeared in the New York Times in 1913, 50 years after the famous battle. The headline proclaimed “how one brave battery,” Dow’s Battery, saved Capt. John Bigelow’s 9th Massachusetts Light Battery at the Trostle Farm at Gettysburg.

“Bigelow is wounded; one of his lieutenants is dead,” the article reports. “About the Trostle farmhouse lie men and horses, dead and dying, while Confederate shells and bullets shriek through the air, shattering and maiming all in their path.

“Suddenly there is a yell. Men in blue burst from the nearby woods. Six guns are unlimbered in no time and trained on the Confederates. There is a cloud and a roar. Canister, double charges of it, comes smashing into (Confederate Gen. James) Longstreet’s ranks, plowing holes in them, piling them on the ground, sending them scurrying for cover.”

The commander of that battery was Edwin Dow.

Dow told the Times reporter, Robert L. Brake, that he and his men faced the 21st Mississippi, which put up a stiff fight, but were pushed back. The 6th Maine lost 14 men in the battle.

The next day, July 3, 1863, Dow’s battery was told to hold their fire as Gen. Robert E. Lee opened fire with “terrific cannonade,” Dow told the Times reporter.

“It was mighty good that we did, for soon (Maj. Gen. George) Pickett’s division appeared over the ridge in front and came charging straight at us,” Dow told the reporter. “I tell you, it looked bad when those Confederates went at our men over there to the right, but glorious (Maj. Gen. Wilfred) Hancock was there with the Second Corps and we beat them, as you know.”

Two of Pickett’s generals were dead and two others were wounded and the Rebels made haste to the rear, Dow recounted. Only a few succeeded, he said “because our artillery continued to mow them down.” A Vermont brigade countercharged, surrounding the remaining troops and forcing them to surrender.

After Gettysburg, the tide of the war had decidedly turned against the South. Dow, later stricken with malaria, was awarded the rank of brevet major by the U.S. Congress for gallant and meritorious conduct at Gettysburg.

On May 3, 1865, the 6th Maine Battery left City Point, Va., Grant’s headquarters during the war, to commence its homeward march, according to the Web site sixthmaine.org. By the time the men returned home to Augusta on June 7, 1865, they had served 3 1/2 years.

Doug Harlow — 474-9534

dharlow@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story